Land

The formation of the Werribee River catchment is a fascinating physiographical tale.

More than 50 million years ago, the Werribee River was merely a stream flowing westwards to join the Moorabool River. This explanation was outlined in Condon’s treatise on the geology of the lower Werribee River 19511.

In those times, the coastal plain sloped from the highlands to the coast and stretched from Lal Lal in the West, to Keilor in the North-East. The course of the streams was affected by the way in which they reached the plain from the highlands, by the slope of the plain and by depressions in the surface of the plain. The streams flowed over this plain in a southerly direction, depositing sands, clays and vegetable matter later forming lignite.

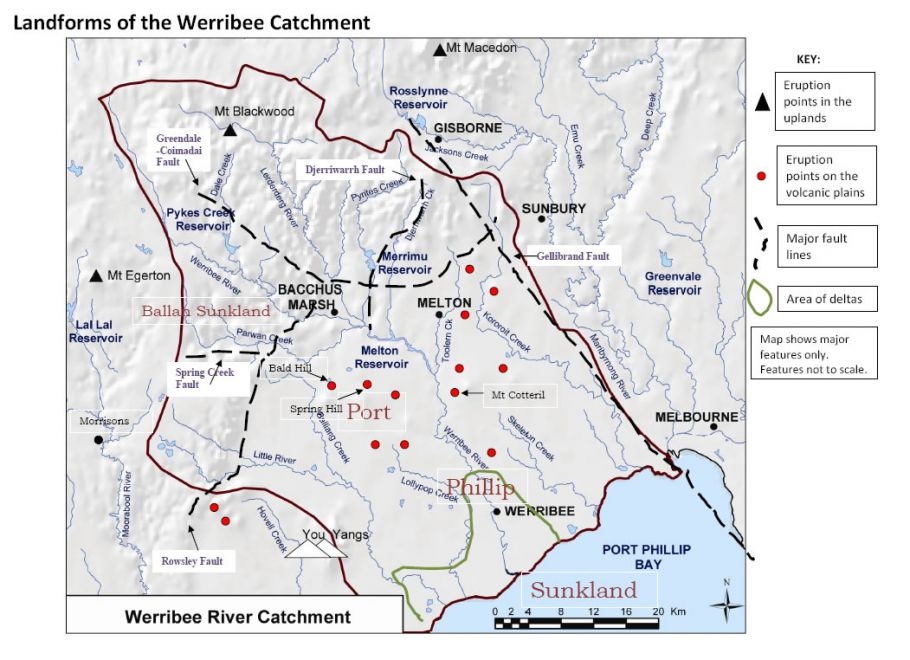

Then, geological activity saw the plain uplifted in parts and dissected by the streams, and volcanic flows filled some depressions and valleys. The Port Phillip basin was formed as a ‘sunkland’ by subsidence, and the streams laid down other deposits such as clays, limestone and sands.

In those times, Condon explained, the Korweinguboora and Korjamumnip1 (sic) Creeks joined the Werribee River and met the Moorabool River near Morrisons. The Dales, Korobeit and Myrniong Creeks flowed to the south, perhaps joining somewhere towards the coastline. The Lerderderg River, Djerriwarrh and the Coimadai Creeks ran independently to the coast.

About 5 million to 2 million years ago2, a new age of volcanic activity took place. During this time lava filled many valleys and spread over the plains. In the Balliang area, flows from Bald Hill and Spring Hill blocked and diverted streams from Ballan to Korkuperrimul to the east, where they joined the Werribee River, and met with the Lerderderg River in the area around Bacchus Marsh.

Then about that time more earth movements took place and the Rowsley, Greendale and Spring Creek faults became active, causing increased cutting into uplifted land and leaving deposits as aprons at the base of the scarps. Then more lava flows from Spring Hill and other sheet flows from Mt Cotteril blocked the Werribee and caused it to form a lake. Bald Hill flows of lava turned the Parwan Creek so that it joined the Werribee River.

However, all of the streams were able to use the sediments they carried from the highlands and the uplifted fault areas to cut through the newly formed hard basalt, forming the Bacchus Marsh basin and aiding the river work its way through the newly formed basalt to the softer sediments below. So the volcanic gorges were formed.

Later, the river was forced to drop its sediment load in the lower stretches of the river when it neared the sea by a rise in sea level. This action filled the river valley and surrounds with sediment, forming a delta. A subsequent drop in sea level caused the river to cut a deep channel in the delta as it continued its way to the sea.

The original inhabitants called the river ‘werribee’, or ‘backbone’3, possibly due to the way it snaked its way across the plains or for the way it was deeply incised into the landscape. Once a westerly flowing stream; the Werribee now presents itself as the major river of the catchment, heading to Port Phillip Bay in a south-easterly direction.

References:

1 Condon, M.A The Geology of the Lower Werribee River, Victoria

Proceedings of the Royal Society of Victoria p. 5-6, Vol 63 1951

2 Dalhaus, P. et al Victorian Volcanic Plains Scoping Study p.12, CSIRO October 2003

3 James, K & Pritchard, L. Werribee the First 100 Years. Werribee District Historical Society 2008 P.7